Printing Industry Exchange (printindustry.com) is pleased to have Steven Waxman writing and managing the Printing Industry Blog. As a printing consultant, Steven teaches corporations how to save money buying printing, brokers printing services, and teaches prepress techniques. Steven has been in the printing industry for thirty-three years working as a writer, editor, print buyer, photographer, graphic designer, art director, and production manager.

|

Need a Printing Quote from multiple printers? click here.

Are you a Printing Company interested in joining our service? click here. |

The Printing Industry Exchange (PIE) staff are experienced individuals within the printing industry that are dedicated to helping and maintaining a high standard of ethics in this business. We are a privately owned company with principals in the business having a combined total of 103 years experience in the printing industry.

PIE's staff is here to help the print buyer find competitive pricing and the right printer to do their job, and also to help the printing companies increase their revenues by providing numerous leads they can quote on and potentially get new business.

This is a free service to the print buyer. All you do is find the appropriate bid request form, fill it out, and it is emailed out to the printing companies who do that type of printing work. The printers best qualified to do your job, will email you pricing and if you decide to print your job through one of these print vendors, you contact them directly.

We have kept the PIE system simple -- we get a monthly fee from the commercial printers who belong to our service. Once the bid request is submitted, all interactions are between the print buyers and the printers.

We are here to help, you can contact us by email at info@printindustry.com.

|

|

Archive for the ‘Digital Printing’ Category

Sunday, April 23rd, 2023

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

A reader of the PIE Blog posted a comment recently describing problems that have occurred in his transition of some titles from offset printing to digital printing, mostly insofar as his digitally printed halftones (and presumably any area screens) printed lighter than expected.

For my response to this reader, I assumed (from the wording of his question) that he was referring to print books produced on uncoated paper using laser printing technology (also referred to as xerography or electrophotography).

Here’s the reader’s question as well as my answer:

Question:

We have run into problems when moving titles from offset to digital. All grayscale images. Contrary to my expectations, digital print images look washed out, losing in my estimation 10% or more (so a 20% screen looks like 10%). Is this your experience? What is the best strategy for converting existing pdf file to digital print (do we have to go back into InDesign and reprocess all the images?).

Answer:

Thank you for your comment. I can usually tell the difference between digitally printed text, screens, and halftones, and offset printed text, screens, and halftones. To me digital screens and halftones just don’t seem as crisp. Also, the transitions in digital screens and halftones don’t seem as consistent (or even) as those printed via offset lithography.

That said, I have seen a lot of really good inkjet work on coated stock (usually posters). So it is probable that the uncoated vs. coated substrate (print books vs. posters) makes a difference, as does the specific digital technology (laser printing vs. inkjet).

In your case it sounds like you are digitally producing print books (which as I note may be of a lesser quality than offset printed books). With this in mind I would suggest that you request samples from your printer (to help you evaluate the technology), check into the HP Indigo electrophotographic press (a laser-based printer of very high quality that uses toner particles suspended in fuser oil), and ask the printer to gang up a number of photos you have darkened a bit in Photoshop to mitigate the problem.

Ask for suggestions as to whether to darken highlights, midtones, and shadows or just the shadows (there may be a less than even transition, and you don’t want to go from overly light to overly dark images). Making some test sheets (and even trying this test with different commercial printing shops) may help you.

I wish I could say this was simple. For print books you are already producing, your printer may be able to make simple changes to the PDF files directly in PitStop (a preflight program) without your needing to go all the way back to the Photoshop files and then reimport them into InDesign before creating the press-ready PDF files.

So the short answer is to set up a test with the print provider to measure just how much lighter the halftones and screens are than expected (i.e., as created) and then to adjust halftones globally (going forward) using Photoshop. Plus, it may be possible to adjust current halftones slightly at the printer using preflight software.

More Thoughts / More Research

After I sent my reply to the reader and posted it online, I did some more research, which I’d like to share with him and with you.

First of all, a lot of the problems reflect the difference between laser printing and inkjet, and between uncoated paper and gloss coated paper.

But first I’ll start with the reader’s probable motivation for choosing digital printing over offset printing, and his resulting need to control the density of halftones, area screens, and gradations. Most probably it was a print book with a limited press run. Such a book is more economical to print digitally because of the absence of extensive make-ready work needed for offset printing.

As another example, I have a client who needs 50 copies of a 184-page book at present. This is ideal for digital laser printing. While the unit cost of the copies will be high, the overall cost of the entire 50-copy print run will be far less than a comparable print job produced via offset lithography.

(Of course the other reason to choose digital technology is for variable-data printing, which is ideal if there must be a level of personalization from copy to copy.)

The Technology

The technology makes a difference as well. Laser printing, particularly dry laser printing (in which flecks of dry toner are attracted to the printer drum with an electrostatic charge, and then transferred to paper, and then bonded to the paper with heat and pressure) can (in my experience) become problematic because the toner flecks may not be as precisely placed with this digital technology as are halftone dots of printing ink in offset lithography. This can cause a fuzzy or ragged look to laser-printed type and images.

Plus, occasionally there are artifacts in digital printing. These are unintended specs or marks that mar an otherwise pristine halftone, area screen, or gradation. Some digital presses seem to be more prone to this than others. And some values (darker or lighter) in black and white images, or some colors in color images, seem more prone to this.

On the positive side, many high-end digital toner presses are available now. I personally like the HP Indigo, which uses toner particles suspended in fuser oil rather than dry toner particles. I have seen excellent results from this digital press, and I believe a number of other vendors have manufactured similar presses as well.

In addition, there’s always inkjet digital printing. When you look at laser printed samples, you’ll see halftone dots on a regular grid (very similar to the halftone dots of offset lithography). In both offset and laser digital halftones, the halftone dots are larger or smaller depending on the amount of a particular color needed (cyan, magenta, yellow, and black).

In contrast, inkjet-printed halftones are dithered. The halftone dots are not larger or smaller. They are all the same size (minuscule). There are just more of them in areas of denser color. So the overall gradations between colors and between values look almost like a continuous tone image (i.e., they are smoother than laser-printed images).

In short, the choice between digital laser technology and digital inkjet technology could help mitigate this PIE Blog reader’s problem with his print books.

The Paper

Paper makes a difference, too. I’ve seen inkjet printing on gloss coated stock that looks as good as offset commercial printing (just as I have seen toner-based digital printing on uncoated offset paper that is lighter than desired, with uneven gradations and occasional artifacts). The PIE Blog reader might want to experiment with paper substrates (depending on his client’s needs).

Photoshop Controls

I had encouraged the reader to select test images and print them digitally after discussing his concerns with his printer. While a simple solution may involve just darkening the images a certain amount on a consistent basis, this may not be enough. The reader may need a more nuanced solution.

For instance, it is possible to selectively increase or decrease the tones of an image in Photoshop using the “Curves” tool. This tool displays a grid with a diagonal line running from the bottom left to the top right (showing initial tones and the new tones to which you will lighten or darken them). This pertains to both black and white images and color images.

By adding control points (or points) to this diagonal line (you can find out how to do this online) and then pulling them up or down (to change the diagonal line on the grid into an “S” curve), you can selectively lighten or darken the quarter tones, halftones, and three-quarter tones of a photo. That is, you can individually tweak the various levels in a halftone image from the lightest lights through the middle tones up to the darkest darks.

The key here is to run tests (physical printouts) with your commercial printing supplier and then apply what you have learned to all subsequent halftone (or area screen and gradation) work.

One of the articles I found also showed a gray scale that transitioned in equal steps from white through grey to black in 10 percent increments. The PIE Blog reader could create a scale like this and then have his custom printing vendor print the scale on both uncoated paper and coated paper, using both laser digital technology and inkjet digital technology. Then the PIE Blog reader could make decisions for future work based on an analysis of the resulting test sheets.

The Takeaway

Here are my suggestions for those of you with a similar problem to that of the PIE Blog reader:

- Involve your commercial printing vendor early. You may even want to find an ally in the printer’s prepress department. No one will be more knowledgeable (both in general and in terms of that printer’s specific equipment).

- Create tests (inkjet and/or digital laser on various paper substrates). Based on these tests, develop a standard operating procedure to lighten or darken images in Photoshop.

- Don’t assume that such problems (with lightness or darkness of images) will be evident across all values of a halftone. You may want to selectively change highlights, midtones, and shadows using such Photoshop tools as Curves.

Posted in Digital Printing, Photos | Comments Off on Custom Printing: Problems with Digital Halftones

Sunday, January 22nd, 2023

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

I would like to begin by saying that there is no right answer to the question I’m about to pose. Rather there is, perhaps, just an approach to answering it in your own print buying and design work. The question is, “How do you determine quality when choosing offset commercial printing vs. production inkjet?”

First a definition. What is production inkjet? It is the blending of inkjet technology with the traditional durability of offset printing presses along with increased custom printing speed. It is a good choice for short- and medium-run print books and magazines and particularly for variable-data work. Production inkjet is not your traditional large-format inkjet press made for wall banners, car- and bus-wraps, and such. It is a hard-core, real commercial printing press in a durable frame.

A Little Background on My Client

In this context I recently bid out a 256-page, 1,000-copy or 1,500-copy, perfect-bound print book for a husband-and-wife-owned publishing house client of mine. In an environment in which perfect-bound books with French flaps, hinge scores, and other elements of superb print production are expensive when compared to the cost of digital electronic books, my clients choose to give their readers the tactile experience of reading. The feel and smell of the paper. The joy of reading a print book.

Pricing for this print book came back to me from three vendors, and one, which was the low bid, had a notation on the bid about J Press printing of the cover. The J Press, which I researched in detail, assuming initially that it was a digital inkjet (production inkjet) press, is made by Fujifilm. Its main selling points, in addition to its variable custom printing capabilities, are its color gamut (even with only four process inks), its flexibility in acceptable printing paper choices, and the minimal set up time (especially when compared to offset commercial printing). Within certain run lengths, all of this translates into high quality and lower costs.

Needless to say, since my clients, with whom I have worked for more than a decade and therefore whose goals for visual and tactile quality I understand and appreciate, had to be comfortable with the technology. The lower price point would not be a good enough reason to choose this vendor.

Moving Toward a Decision

The first thing I did was ask the book printer to send a comparable printed sample to my clients. I knew that nothing would help them make a decision regarding offset printing vs. digital inkjet printing as well as a physical sample. The reader’s eyes and fingers don’t lie.

I also asked the printer to send a sample because I had seen numerous inkjet printed products, and while their color gamut was extraordinary, with vibrant hues and subtle transitions between colors, I had seen in some inkjet samples a lack of crispness in detail. This concerned me. They were not as sharp (the contrast between adjacent edges of color or value) as the offset printed products I had been used to. Without knowing more, I had wondered if this was due to the differences in ink composition and printing paper. After all, inkjet ink is thinner than offset ink. Inkjet ink in this case is also water based unlike oil-based offset inks. (Granted, this had nothing to do with the color range or color fidelity, which I had come to believe usually was equal to that of offset printing.)

I had assumed that the thinner ink would have been more likely to seep into the paper fibers (in contrast to the thicker, oil-based offset ink, which sits up on the surface of the paper). This is called ink “holdout.” It makes for a crisper image and more detail, as well as more vibrant colors.

But when I researched the Fujifilm J Press, I learned that it would also accept more paper substrates than other inkjet printers (including coated paper), that even with only a 4-color inkset it had a remarkable color gamut, and that it incorporated improved ink coagulation technology and heat-based ink drying technology (presumably to allow even an aqueous-based, thinner-than-offset ink to dry or cure on the surface of the paper without bleeding into the paper fibers).

So I decided to keep an open mind and see what my client thought of the printer’s J Press-printed sample (which turned out to be a glamor-based magazine, a perfect-bound book just like my client’s art books of poetry and fiction). The reason the subject matter is relevant is that glamor, food, and automotive are the three best subjects with which to judge both photography and commercial printing. These are subjects that require consummate precision in everything from the photographic lighting to the custom printing technology, and these particular clients (and their marketing agencies) usually spare no expense to ensure quality.

Now we will see what my clients think.

Keeping All Options Open

I have no vested interest in selecting this printer over one of the other two, other than the fact that I have worked with them for many years and trust their quality and integrity (actually good reasons, beyond price, to choose this vendor).

This vendor also has offset printing capabilities. Plus one of the other two printers is very costly, and the other is less expensive but not as willing to absolutely commit to a schedule (in these times of paper shortages, when printers are often taking much longer than in the past to produce custom printing jobs).

So these are the next steps, as I envision them.

My clients have seen the initial sample glamor catalog. They like the brilliance of the color, but they are a little concerned about the images, which seem to be of a slightly softer focus than they would like. They are not sure that this is not intentional, since soft focus is sometimes intentionally used in glamor photography.

Because of this concern, I have asked the printer to provide pricing for a single proof of my client’s actual print book cover on the Fujifilm J Press. If my client likes the sample, we have our printer.

Plan B would be to ask this printer for prices for offset printing the book. This will be more expensive, according to the sales representative. That said, my next questions are more nuanced:

- Since the press run will be 1,000 or 1,500 copies of a 256-page book, I believe we may be at the crossover point at which an inkjet-printed book becomes more expensive than the same book printed via offset lithography (after all, at 1,000 x 256 pages or 1,500 x 256 pages this is a sizable run, and inkjet printing is economically beneficial primarily for shorter-run printed products). Plus, we’re comparing one vendor’s inkjet-printed product to two other vendors’ offset-printed products. We actually don’t know yet that the vendor with the J Press won’t still provide lower offset-printing prices than the other two printers when we shift the pricing model from digital to offset.

- Or, we even may have the option of doing a hybrid job: an offset-printed cover (a short run of 1,000 or 1,500 covers) bound to a digitally-printed book text block. This might cost less than a fully-offset-printed book while still retaining the consummate quality of offset printing for the four-color cover. After all, the interior of the book is, presumably, just black text on a page with no screens or photos. This would be ideal for inkjet printing.

The Takeaway

You may say that this is putting the cart before the horse, adjusting everything to work with a specific commercial printing supplier. But from my vantage point it takes into account that not all printers are as committed to quality and schedule as this one has shown itself to be in past jobs.

Fortunately I also have the luxury of time. I can make sure that my clients see samples until they are either satisfied or ready to move on to an alternate printer. Also, regarding schedules, this particular printer will produce the book in less time than the vendor with the mid-level price but more slowly than the most expensive printer. A longer schedule may compromise my client’s ability to prepare the manuscript and have the book designed and final art files prepared in time. This is because my client’s book distributor has provided an inflexible, hard deadline.

So there are a number of considerations beyond money, including the technology to be used, the schedule, and the quality of the printed product. In your own design and print buying work, I would encourage you to give thorough consideration to all of these factors.

Posted in Digital Printing | 2 Comments »

Sunday, January 15th, 2023

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

What is a giclee? Actually, the word, which is derived from the French, means to “spray, spout, or squirt” (Wikipedia). It refers to a high-end inkjet print used as a work of art (perhaps like the one printed above).

Back in the 1980s when I was a graphic designer, inkjet was a very new technology. Instead, analog color prepress proofs (Matchprints, Color Keys, and Cromalins) were made from mixed color powders or overlays on a base that was different from the final selected commercial printing paper.

So late in the ‘80s when I started reading about IRIS proofs, and seeing them when our custom printing sales representatives delivered prepress proofs, I was impressed.

And so were a lot of other people, among them fine artists. In the late ‘80s the artists’ community needed a way to reproduce original artwork for sale. For instance, a large, $4,000.00, one-of-a-kind painting might be reproduced in a series (a limited run of high-quality reproductions) for maybe a third of the price of the original.

There has always been a market for prints. I myself have many lithographs (actual art prints without halftone dots but made in a way similar to offset lithography), as well as serigraphs (screen-printed pieces produced with multiple mesh screens each printing a single color on a base paper substrate).

The IRIS Phenomenon

Prior to the inkjetting technology of such printers as the IRIS, these were the options for an artist who wanted to produce multiple copies for sale from a “matrix” (usually but not always a printing plate of some kind): lithographs, engravings, etchings, and custom screen printing. So the IRIS opened up a number of options.

Artists and galleries worked to resolve the two main problems with Scitex’s (eventually bought by KODAK) IRIS inkjet process. The process, which involved wrapping the commercial printing substrate around a metal drum and then jetting colored ink onto the paper, had to be modified for thicker media (such as canvas). And then the image produced via the inkjetting process (which faded over time) had to be made more stable.

After all, when I was getting IRIS proofs from my commercial printing supplier in the late 1980s and early 1990s, all that I (like other designers) needed was to check critical printing color in a continuous-tone (as opposed to halftoned) proof. The proof itself was irrelevant once the job had been printed and delivered.

But the IRIS held promise, in spite of its higher than $100,000.00 price tag, and artists had a new technology to use along with screen printing and etching for a limited series of salable art prints.

The Move to Large-Format Inkjet

Eventually it was no longer necessary to depend on the single IRIS technology. Overall, inkjet technology had improved, and companies such as HP, Canon, and Epson were offering large-format inkjet equipment at a lower price point than the IRIS. Equipment using dyes or fade-resistant, pigment-based archival inks, as well as substrates such as watercolor papers, coated and cotton canvas, and vinyl, replaced the former IRIS technology of choice.

These were now not only archival prints (created using technologies and materials that yielded final art prints with an exceptionally long life span), but they also provided a wider color gamut than before.

For instance, instead of just the four process colors (cyan, magenta, yellow, and black), large-format inkjet printer manufacturers such as Epson, HP, and Canon offered up to 12 colors in an extended inkset, all available at the same time on their inkjet equipment. These might include light magenta; light cyan; maybe an additional photo black; or red, green, and blue; or violet, orange, and green. All of these provided a much wider color gamut (more distinct colors) than a 4-color-only (CMYK) inkset. They also allowed for more subtle gradations from one color to another.

The Marketplace

When my fiancee and I go to the thrift store, we often see framed prints that look like originals. However, under a 12x printer’s loupe I can see the halftone dots of the offset lithographic process. This is different from both a traditional lithograph and a high-end giclee (inkjet print). And given its customarily lengthy press run, the individual offset lithographic prints are not worth much.

In contrast, individual copies from a traditional lithographic run (of maybe 250 copies) are worth a lot more (depending on the esteem in which the artist is held, whether the prints are signed, etc.).

The same is true for a giclee print. In this case, the artist has just used a digital process for creating multiple copies rather than a serigraph screen or etched copper plate. She or he has used the finest archival inks and acid-free paper or canvas, and has been closely involved in the production of the limited edition. Hence, the signed copies do have value, and they will last a long time, just like the prior editions of serigraphs, engravings, lithographs, and such.

Moreover, a fine artist might choose to print copies of the fine art piece one at a time as they are purchased (perhaps a color-corrected, high-quality photographic image of a large oil painting that might otherwise sell for $4,000.00). And the buyer is happy because she or he can afford to buy a piece of art for maybe a third of the price of the original oil painting.

So overall, the production process is much more under the control of the artist, and the prints are much more affordable to the buyer. Plus, the process of giclee custom printing can provide copies of photographs, flat artwork, and even computer-generated art, all meticulously color corrected and color controlled by the artist.

Valuation

Having collected serigraphs, lithographs, monoprints, and such, over four decades, I initially had a distrust for this technology. “How can this be any more valuable than one copy from a press run of many offset-printed posters?” I thought. But over time I came to view giclee custom printing as nothing more than a controllable technology suited for producing a limited run of archival prints, just as the prior technologies had done. I realized that if I couldn’t afford a $4,000.00 oil painting, I could at least afford a giclee at a third of the price. And I knew that the artist’s involvement in the process (attested to by her or his signature and the numbering of copies in the limited press run) had been confirmed.

With this in mind I was interested in the advice I saw online from a number of artists and galleries as to the process of valuing giclees. The general consensus is that artists should factor in all expenses, including materials, time spent in the creation of the giclee, color scanning and correction of the original, and a reasonable amount for profit. That said, the key determinant would also be the renown of the specific artist in question, or how well regarded she or he is by peers and patrons.

It’s a little like pricing your graphic design work. If you’re good, and well known, you can charge more. After all, the value of a piece of art is what a willing buyer will pay to acquire it from a willing seller.

That said, many of the articles also included pricing grids (as a starting point), noting low-end, median, and top-end pricing of giclees based on their size (say 8” x 10” vs 36” x 48”).

And, of course, the press run makes a big difference as well. If you’re an artist and you’re selling 50 copies of your giclee work, you would command a higher price per copy than you would if the press run were 250 copies (the same idea as a custom screen printing or etching run of 50 signed copies rather than 250 copies).

Again, giclee is just the technology used to accurately print a limited run of color-corrected, archivally produced art prints, just like the lithographs and even the IRIS prints that preceded the current spate of Canon, Epson, and HP large-format inkjet giclees.

Posted in Digital Printing | Comments Off on Commercial Printing: High-end Inkjet for Fine Art Prints

Thursday, September 8th, 2022

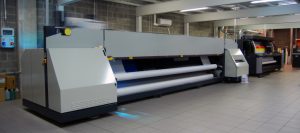

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

“Production inkjet.” When I hear the word “production,” I immediately think high volume. The company, or industry, is serious about getting the work out.

When I used my first inkjet printer, I was an art director/production manager for a large non-profit educational foundation. It was the ‘90s. The inkjet was slow, and the colors were somewhat garish, but we were happy to be able to see the overall look in mock-up form. The output was good enough for us to visualize the printed end result and communicate this appearance to clients. We were grateful.

Over the ensuing decades the quality of inkjet color improved dramatically, and the speed increased as well, but compared to offset commercial printing it was not adequate. Here’s a random comparison from one online writer. A laser printer can produce 100 pages a minute. An inkjet printer can produce 16 pages per minute. An offset press can produce 18,000 sheets per hour (300 sheets per minute). Moreover, since some offset presses accommodate 28” x 40” press sheets or larger, you can get a lot of pages, laid out side by side, printed in that 18,000-sheet-per-hour window of time.

Granted these are general numbers, but the comparison is not only relevant but also true in my experience. Inkjet is slow when compared to other printing technologies. The color is spectacular, due in part to all the additional colors beyond cyan, magenta, yellow, and black that many inkjet presses use, and the resolution is great. But they’re slow.

On the plus side, however, there are characteristics of inkjet printing absent in offset lithography. Inkjet presses can include variable data, and due to the minimal makeready (when compared to offset lithography), they are exceptionally economical for short press runs.

But The Issue with Speed Is Changing Now

I just read a few press releases from Kodak about their new Prosper 7000 Turbo Press, and the development of the technology is very encouraging. In fact, production inkjet may well be the future of commercial printing. Color fidelity is, and has been for a while, extraordinary, but the speed of this custom printing technology (as that word “production” suggests) is now increasing significantly as well.

Speed, quality, number of available paper substrate options. All of these are pertinent to the recent improvements in production inkjet. To put this in perspective, let’s say you’re printing a thousand copies of a 300-page print book, you will want the text to be clear and the photos to be crisp and detailed. But you’ll also want the overall time on press to not be excessive (or, as noted above, 300 pages x 1,000 copies at 16 pages per minute).

According to their press release, Kodak is now meeting these goals with the Prosper 7000 Turbo Press.

Here’s a description of its capabilities:

- Up to 5,523 A4/letter pages per minute.

- Far more substrate options than before, including newsprint, coated and uncoated papers, specialty papers, and recycled papers.

- Variable quality (affecting both speed and resolution, inversely), which allows the printer to match the job to the specific visual requirements. (A newspaper, for instance, doesn’t require the same level of quality as a promotional piece. Nor does a textbook need the same level of quality as a promotional piece.)

- Sustainability. “The Prosper 7000 Turbo Press uses eco-friendly, water-based Kodak nanoparticulate pigment CMYK inks,” which support “efficient drying even at peak press speeds” (“Kodak Announces Fastest Inkjet on the Market with Kodak Prosper 7000 Turbo Press,” 06/16/2022 press release from Kodak).

Let’s break this down. First of all, unlike most of the inkjet presses you may have seen (including office inkjets and even the large-format inkjet presses that produce signs), the Prosper 7000 Turbo Press is a web press (i.e., roll fed). Like a heatset web press used for offset lithography, it is designed to move very quickly.

However, speed isn’t everything. If the ink weren’t to dry quickly, all would be lost. But with the Kodak Prosper 7000 Turbo Press, the equipment is set up to dry the ribbon of paper traveling through the press using near infrared technology (NIR). This ensures that ink dries quickly on the surface of the press sheet.

Why is this important? Because it allows for thicker ink films, like those used in offset commercial printing. Denser ink coverage contributes to the striking color. Granted, all of this is either better or worse depending on the variable speed and resolution. (Kodak Prosper 7000 Turbo has three modes: Quality, which is similar to offset and which uses a 200-line halftone screen; Performance, which uses a 133-line screen and is good for textbooks; and Turbo, which uses an 85- to 100-line screen and is good for newspapers with low ink coverage.) This variability addresses both quality and overall ink coverage, maintaining the best resolution and speed for the specific output needed.

Why Should I Care?

Before I go any further, this is why I think this is relevant. Because a quick, accurate alternative to offset custom printing that allows for short and longer runs and also variable data printing will move a lot of jobs that had been printed on offset equipment onto digital equipment. This will not only enhance the quality and options for custom printing, but for a lot of jobs this will also save money. And (as Kodak notes), with supply chain issues and increased costs for offset prepress consumables, this will help printers (and hence their clients) measurably.

More Specs

Here are some more features:

- The throughput of 5,523 A4/letter pages translates to a printer “almost 35% faster than its nearest competitor” (“Kodak Announces Fastest Inkjet on the Market with Kodak Prosper 7000 Turbo Press”).

- The paper range is 42 to 270 gsm. Check this on a calculator. It allows for text and cover weights.

- The web width is 8” to 25.5”; cut-off is up to 54”. What this means is that for press signature work such as print books, you can get more pages on a roll of press stock in proper signature layout to allow for folding and trimming into larger press signatures, and therefore you can produce your print book work faster.

- The press is meant to be run 24 hours a day, every day, with a 200-million-page duty cycle per month. That means the press is durable and meant for hard use. So it’s not going to sit idle while you wait for repairs.

The Takeaway

Interestingly enough, with automation and increased productivity, offset presses can do shorter press runs efficiently. At the same time, production inkjet presses like the Prosper 7000 Turbo Press can do longer press runs efficiently. (The two technologies are gradually approaching one another in terms of speed and flexibility.)

I don’t think either technology will cease to exist, with one eclipsing the other completely, at least not anytime soon.

I think that digital inkjet (both production inkjet and grand-format inkjet) and the increasingly efficient offset printing (with automated plate changing, and closed-loop, electric-eye color monitoring and calibration) will both thrive, with each being appropriate for different work. After all, you’re not going to produce variable data work on an offset press, and you’re not going to produce 500,000 copies of anything on a digital inkjet press.

In my view the takeaway is that you should study both technologies and decide which works for each type of job you’re producing. Ideally, you should find the best vendor for each technology, and then select the right one for the specific commercial printing job at hand.

The more you learn about all of this, the more ready you will be for the future of commercial printing. And, in my reading, I’m seeing that in spite of current paper shortages, both offset and digital printing have a spectacular future coming. At least that’s what I see in my crystal ball.

Posted in Digital Printing | 2 Comments »

Sunday, May 8th, 2022

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

A client of mine came to me this week with a question, “Can you print directly on kraft paper tubes?” She is the senior VP of design at a firm that makes, packages, and sells lip balm. She didn’t want to print and affix labels to the cardboard tubes. (more…)

Posted in Digital Printing | Comments Off on Custom Printing: Printing Directly on Kraft Paper Tubes

Thursday, February 10th, 2022

There are many online printing companies out there in the market, and each one claims to be the best in the industry. In a situation like this, how to figure out one of the best online printing companies that can provide you with quality services at an affordable cost?

This infographic will help you with some important tips on how to select the best service provider in the entire town. So, what are you waiting for? Let’s dive in! (more…)

Posted in Digital Printing | 1 Comment »

Thursday, November 18th, 2021

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

To reverse the common maxim, “Every silver lining has a cloud.” This also holds true for digital custom printing, the relatively new technology that has brought to commercial printing both a much wider color gamut than offset printing and the ability to make each printed piece different from every other piece in the press run. (more…)

Posted in Digital Printing | Comments Off on Commercial Printing: Sidestepping Flaws in Digital Printing

Sunday, October 31st, 2021

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

About twenty years ago when I was consulting with a congressional publisher I attended a birthday gathering at which I saw my first printed cake. I had a hard time wrapping my brain around the concept. I couldn’t picture how it had been done. Inkjet, I assumed, but I couldn’t envision the print heads elevated over a three-inch-deep sheet cake. Also, I thought about the health issues. How could you print on a cake and not compromise the health of those who ate it? (more…)

Posted in Business Cards, Digital Printing | Comments Off on Custom Printing: Printing Photos and Type on Cakes

Monday, March 29th, 2021

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

I’m not a gearhead. I don’t get excited about car specifications or even computer specifications, but when it comes to custom printing, I’m actually getting very excited about the developments in digital printing. In this arena, I do get pumped about equipment specs. (more…)

Posted in Digital Printing | Comments Off on Custom Printing: Kodak’s New Production Inkjet Press

Monday, November 30th, 2020

Photo purchased from … www.depositphotos.com

Designing for digital printing is a subject that needs regular attention these days. Digital and offset printing are not the same. While each has its benefits, they both have potential drawbacks that you can minimize based on your approach to the design of your custom printing project. (more…)

Posted in Design, Digital Printing | Comments Off on Custom Printing: Designing for Digital Printing

|

|